There have been big changes for drivers in Bristol city centre. This post sets out the details, outlines the impact on drivers and investigates the broader picture.

Changes for drivers

There have been a number of closures to general traffic:

- Bristol Bridge and Baldwin Street

- Union Street – closure of the route to Rupert Street

- Old City (after 10.30 am each day) and King Street

- Cumberland Road – closure inbound from October 2021)

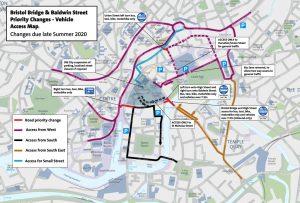

The effect of these changes is to bar through-journeys from one side of the inner loop road to the other, whilst allowing access to everywhere within the loop. (See Bristol Bridge and Baldwin Street vehicle access map.)

A lane has been removed for general traffic:

- from Park Row to Marlborough Street

- on Lewins Mead

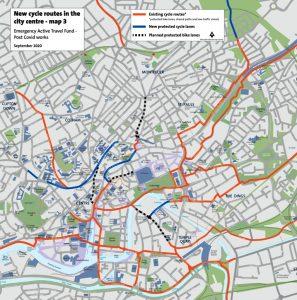

The street space has been given over to a bike lane or a bus lane, helping to free up buses and fill in gaps in the network of protected bike routes. (See New Cycle routes in the city centre map.)

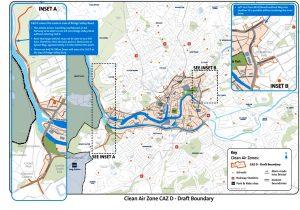

A Clean Air Zone (CAZ) will be introduced from October 2021 as follows:

- covering the area within the inner loop road

- affecting pre-2016 diesel and pre- 2005 petrol vehicles (about 25 to 30% of vehicles)

- charging older cars £9 per day

- exemptions (initially for 1 year only) for disabled drivers, in-zone residents, low-income city centre workers, hospital visitors

- enforced by cameras

- in place until roadside NOx levels get below legal limits – projected by end 2023.

(See Clean Air Zone map).

The impact on drivers

There are a number of impacts:

- cross-city journeys will become less direct, diverting around the inner loop road

- there will be more traffic and slower journeys on the inner loop road. But the impact of removing a lane may be less than one might think: the flow capacity is determined by the pinch-points at other points on the inner loop road

- some journeys will be displaced to avoid the CAZ charge, creating more traffic on roads outside the city centre. This has been modelled in planning the CAZ, and will be monitored.

- charges will be incurred by those that choose to drive in the CAZ, or have no alternative. And by some who have unwittingly been caught driving on Baldwin Street or Bristol Bridge, not noticing the signs

- some people are concerned that the restrictions will damage footfall for businesses and tourism. But note that the Cabot Circus car park is outside the CAZ.

Bristol has more traffic passing through the city centre than other cities because the M32 brings traffic into the centre and there are fewer outer-ring alternatives than in other cities. The CAZ zone includes Temple Way and the Cumberland Basin flyover, so through-journeys will be affected.

The impact may change over time: it takes months for drivers to adapt their journeys, and some journeys may ‘disappear’, as drivers choose different ways to travel. And overlaid are traffic changes during Covid lockdown, and longer-term post-Covid trends in travel and workplace patterns. Traffic levels returned to 85% of 2019 levels in October 2020, but the daily pattern changed – less commuting and more daytime trips.

The broader picture

So those are the facts: what is the broader picture? Why are the changes being made? How do the changes fit into the Council’s wider transport policy? What are the longer-term goals? How will the politics play out?

Bristol city centre suffers from too many vehicles on its roads, and the expansion in Bristol’s population, and more city centre residents, will increase the travel demand. Curbing private motor traffic in city centres as a policy is common across the UK and Europe. This is not just about how we move around: it is about making streets pleasant places to experience and enhance our well-being. It is recognised that there is insufficient street space to accommodate the huge growth in vehicles over the years, and that public transport and active travel use the space more efficiently and need space to ease their passage. To the extent that drivers switch to other modes, there are fewer cars on the road. Traffic congestion is not only frustrating for drivers but unpleasant for other road users. Air pollution is now recognised as a top public health threat, and traffic contributes to roadside pollution: electric cars will take away NOx emissions but not particulate pollution.

Bristol had no choice in implementing a CAZ, even if it has taken the Council five years to deliver it. Along with other cities, it was belatedly complying with EU rules which pressure group Client Earth took legal action to force the government to address. For a long time Bristol’s Labour administration prevaricated out of concern for the effect on lower income drivers. Then Covid came along, and the government ordered councils to take measures rapidly to enable social distancing and facilitate active travel. In response, the Council chose to bring forward plans for city centre street space changes, in the hope that this would achieve air quality compliance without a CAZ. But the government’s decision deadline of February 2021 gave them insufficient time to demonstrate the effectiveness of the measures.

To be fair, street space changes can be a more effective way of reducing air pollution: Baldwin Street is a good example. And the Mayor was right in encouraging people to use public transport and active travel as a more constructive way of reducing air pollution. Even though a CAZ is useful as a very public way of effecting travel behaviour change, it is arguably an expensive sticking-plaster solution, which has absorbed Council resources too much and for too long.

The Council recognises that the CAZ will cause some displacement of traffic through inner suburbs. In defence, it argues that the acceleration of changes to cleaner cars due to the CAZ will benefit inner suburbs, that the modelled displacement of air pollution is less significant than one might think, and that they will introduce Liveable Neighbourhoods to mitigate the impact. Liveable Neighbourhood schemes include point closures to prevent traffic passing through a neighbourhood whilst retaining access to anywhere in the neighbourhood: it is the same ‘traffic cell’ approach that has been applied in the city centre. Liveable Neighbourhoods also introduce other measures to encourage walking and cycling and improve the public realm, and are now firmly a part of the Council’s plans.

The street space changes in the city centre, including the closure of Bristol Bridge, were foreshadowed in the 2019 Bristol Transport Strategy and the 2020 City Centre Framework policy documents. The latter document specified city centre route networks for public transport including continuous bus lanes; pedestrian routes and priority routes for public realm investment; All Ages and Abilities (AAA) cycle routes.

Also in the Council’s transport plans are strategic corridor schemes that will make street space changes to free up buses on arterial roads, and make cycling and walking safer and more attractive. These are the so-called ‘Bus Deal’ schemes, under which First Bus has committed to increasing bus frequency in return for quicker and more reliable passage for their buses. These schemes are even more important since Covid-19 damaged public transport. The first scheme is route 2, from Cribbs Causeway to Stockwood. Route 2 buses are helped by the closure to general traffic of Bristol Bridge. Over time, the corridor schemes will be complemented by further Park and Ride schemes – progress is frustratingly slow. All these schemes are an essential counterpart to the city centre changes, enabling access to the city centre by sustainable travel modes.

These transport plans have the wider aims of reducing carbon emissions and air pollution. Transport causes over a third of greenhouse gases in the UK, and it has been estimated that motor traffic volumes have to reduce by 40% to meet the 2030 zero emissions target, even allowing for the move to electric cars. Street space measures are a quick and cheap way to help meet that goal. The Council has yet to explain to the general public this bigger picture of its transport plans but it intends to rectify this later in 2021.

In an ideal world, all the complementary elements of the transport plans would be introduced at the same time, but in the real world the progress and timing of these schemes is constrained by the funding available. The city centre street space schemes were brought forward when the government made funding available for active travel schemes in 2020. Nowadays most of the funding for Bristol’s transport plans comes via the West of England Combined Authority (WECA), the sub-regional authority that includes South Gloucestershire and Bath and North-East Somerset. Currently, WECA’s adopted joint transport plan is quite strongly roads-based, but it is under review. The plans for both Bristol and WECA will depend on the outcome of the May elections, with different political landscapes in Bristol and the sub-region. However, the transport plans I have described seem to carry broad party political support.

Surveys show that the majority are in favour of these changes, but it is certain that some changes will meet strong resistance: some people do not like their freedom to drive restricted and they voice their complaint loudly. Recent news reports from elsewhere of protests against Low-Traffic Neighbourhood schemes are evidence of that.

Alan Morris

Like many people I know I will not be visiting Bristol.

The new no private car zones will cause many people visiting Bristol after avoiding city due to Covid, severe problems and lack of familiarity with changes will just allow city Council to collect more money.

This upheaval has actually made my shopping experience much easier. I now do all of it at Cribbs Causeway, rather than attempting to get into Bristol City Centre, as one traffic penalty notice was enough for me! Apologies to all attempting to run businesses out of Cabot Circus, but for many residents living in The Portway area, out of town shopping is now the way to go. And Gloucester Council is welcome to any revenue uplift.

i have recently been caught by the bus gate in baldwin Street. I am a Bath resident and probably travel to Bristol 2 or 3 times a year. This website in discussing the impact of the traffic restrictions acknowledges that ‘ it takes months for drivers to adapt their journeys’. It is a great pity that the system doesnt recognise this and issue drivers which have used this route for years with a warning notice rather than a £30 fine. My visit to Bristol leaves a bad taste. I will probably adapt my journey quicker than your website suggest and avoid visiting Bristol altogether.

As a visitor to Bristol I needed to get to the feeder road for an exhibition this week.

Coming from the west- what a nightmare to negotiate the new private car restrictions!

Sadly I will now not visit the city centre. I am not sure of the incentive to encourage electric cars, if we still cannot get around a city with relative ease. What with all the redirections, one ways, bus lanes, cycle paths , electric hire scooters whizzing around and varying speed limits-all potentially dangerous distractions for drivers !

I feel very sorry for retail in the city centre. After the closure from Covid they are now faced with this ‘green’ scheme. I am not sure that cyclists and electric scooter drivers are going to provide sufficient business for them!

So as a car driver I shall go out of town.

We seem to be in a vicious circle

Years ago these out of town shopping facilities grew. Then complaints about the lack of in town shoppers saw a push to regenerate the town centre shopping experience. Now it will be out of town shopping and online!

I live in Kingsdown on Alfred Place a small residental street on the corner of Walker street . The traffic comes from three directions and piles up on the corner of Alfred Place., It has caused the pavements to be worn away by heavy lorries having to go up on the curb, while traffic jams up and ambulances can’t get through and heavy lorries get stuck and have to try to reverse as other traffic builds up behind them, all while pumping out emissions. It must be one of the most polluted junctions in Bristol at rush hour. I wonder whether there could be a one way system to avoid the impact of the emissions on our community.