An opinion piece by Gavin Smith, former Bristol Council transport planning officer

An opinion piece by Gavin Smith, former Bristol Council transport planning officer

Not since the days of Avon County Council has Bristol had anything resembling a traffic and transport plan for the city centre. Now, with our Mayor, it is again possible.

In my experience as a Bristol City Council (BCC) transport planner until 2011, these are the constraints we work under. BCC in theory is party to a Joint Local Transport Plan with a hierarchy of transport provision, putting pedestrians first, followed in order by disabled people, cycles, buses, delivery vehicles, and cars.

In practice, the hierarchy is exactly reversed. This is because the council as Highway Authority employs a range of teams of specialist officers, of whom top dogs are the traffic signals engineers and a traffic management team charged under the Traffic Management Act 2004 to “make sure that traffic can move freely and quickly on their roads”. The bus team leaves planning to First Bus. Disability, pedestrian, rail or freight planners are scarcely in sight.

The net result: traffic jams, droves of buses getting in each other’s way in the centre, cycle routes that die out, and a city centre designed for neither the disabled nor children.

But just suppose we were to take the hierarchy of users seriously. Could we produce a plan? Yes we can.

It is derived by successively adding layers, starting with the ideal requirements, or my assessment of them, of each user type. Each layer is adjusted so as not to conflict with the others. The outcome is not yet Delft or Gothenburg, but a lot better than we have at the moment.

Pedestrians

Pedestrians have a series of beautiful civic spaces at Harbourside, Queen Square, College Green, the centre, linked seamlessly into each other, as in Bath. Current barriers to pedestrian movement – as between Christmas Steps and St Michael’s Hill – will be ameliorated. The Old City and Harbourside become fully pedestrianised. Greenways and wide clear footways radiate to all parts of the city.

Disabled

Disabled people get much improved crossings of traffic routes, preferential parking spaces within shared space streets, also spaces for coaches to stop.

Cyclists

Cyclists would have segregated Dutch-style cycleways parallel to main traffic routes. In parts of the city centre, cyclists can share space with pedestrians; but in reality it is often better to clearly indicate through-cycleways; that’s what I’ve done, partly in the knowledge of what the Bristol Cycling Campaign is up to.

Buses

Buses have priority on a circuit including Victoria Street, Bristol Bridge, Baldwin Street, Lewin’s Mead, Bond Street and Temple Gate. This would allow multiple interchange points including the centre, Broadmead, Cabot Circus and Temple Meads station. The exact operational characteristics are up for grabs, but this circuit could in future be converted to tram-train operation connecting into the suburban railway lines, as in Manchester or Croydon, or street trams along the old tram routes, as in Nottingham and Sheffield.

A specific city centre bus service could link in the BRI and the West End. Disabled accessible suburban feeder buses stay out in the suburbs, interchanging at Bedminster, Kingswood, Westbury-on-Trym and Fishponds. We would have interchangeable tickets similar to London’s Oystercard.

Servicing vehicles

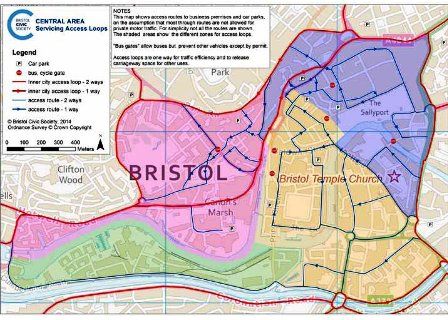

These no longer cross the city centre, except licensed users using rising bollards or automatically controlled gates which are open to buses. These are placed on the centre, Baldwin Street, Park Street, Wine Street and perhaps St Philip’s Bridge and Trenchard Street. Examples can be seen in Grenada and Cambridge.

Through traffic is confined to the Inner Ring Road of Bond Street / Temple Way / Coronation Road / Brunel Way / Hotwells Road; the poor road capacity passing the Bristol Royal Infirmary is met by making Upper Maudlin Street westbound only, paralleled by Lewin’s Mead eastbound only.

Off this circuit, servicing access to all premises is gained via one-way access loops, allowing efficient junctions at the Inner Ring Road, and freeing up carriageway space within the city centre for other purposes.

Cars fit alongside servicing traffic; their excuse for getting into the city centre minimised by the conversion of many central car parks and kerbside space to residents and business only. A workplace parking levy, already in use in Nottingham, generates a cash flow for public transport. Most commuters, as in Delft, now arrive by cycle, train, bus or foot.

None of this is fantastical, it has already been achieved in many other cities.

Gavin Smith

gavinjasmith@hotmail.com